Meili Gupta se trata preguntar otro pregunta.

Gupta, de 17 años, es un estudiante de último año, elocuente y elocuente en un internado de élite de la Academia Phillips Exeter, que es todo menos el estereotipo introvertido y de voz suave. Sin embargo, ella sabe tanto sobre informática como cualquier estudiante de secundaria que haya conocido. Incluso creció fielmente leyendo el MIT Technology Review, la publicación emblemática de la universidad, que muestra, porque Meili es la estudiante asistente más ubicua en EmTech Next, una conferencia que la publicación realizó en el campus el verano pasado sobre inteligencia artificial, aprendizaje automático y "el futuro del trabajo".

Aparentemente, la conferencia es una oportunidad para que ejecutivos y profesionales de la tecnología se codeen mientras determinan cómo las tecnologías de próxima generación darán forma a nuestros empleos y economía en las próximas décadas.

Para mí, la reunión se siente más como una oportunidad de tener una crisis existencial; Incluso podría decir una crisis religiosa, aunque no solo soy un ateo confirmado sino también profesional. EmTech Next, tal como lo experimento, es un referéndum sobre lo que significa ser humano en un momento en que la tecnología está redefiniendo cómo nos relacionamos entre nosotros y con nosotros mismos.

En resumen: ¿los líderes del mañana, a pesar de las buenas y éticas intenciones, utilizarán en última instancia sus herramientas de alta tecnología para explotar a otros de manera cada vez más eficiente, o para encontrar un mejor camino a seguir?

Pero llegaré a todo eso en un momento, incluyendo por qué es tan inusual que alguien como yo asista a una conferencia así, y mucho menos con un pase de prensa.

Primero, de vuelta a Gupta, quien ha venido a la conferencia. preparado. No es que haya completado ninguna tarea específica para la conferencia por adelantado, es solo que cada vez que se acerca al micrófono para iniciar una sesión de preguntas y respuestas con otra mini investigación cuidadosamente compuesta y entregada enérgicamente sobre el destino de nuestras industrias más dinámicas, ella no solo pregunta sobre el futuro del trabajo, ella encarna eso.

"Crecí con un teléfono en la mano", me dijo Gupta en una entrevista realizada durante la conferencia, y "la mayoría de las personas (en mis clases) tienen cubiertas para las cámaras de sus computadoras".

Como editor gerente de la revista STEM de Exeter Importar, Publicó análisis reflexivos sobre los desafíos éticos inherentes a cuestiones como la IA y el cambio climático.. Es un tema que le ha interesado desde que entró al campus: Gupta tomó el curso de nivel superior "Introducción a la Inteligencia Artificial" como estudiante de primer año de secundaria. También tomó clases y aprendió sobre autos sin conductor y visión por computadora, y preparó un estudio independiente sobre algoritmos de aprendizaje automático. Este otoño, comenzó su último año con un curso llamado "Innovación social a través de la ingeniería de software", en el que los estudiantes eligen un proyecto local y desarrollan software para hacer el bien social. (Levante la mano si esto se parece a lo que hizo con su adolescencia).

Y meili hace quiere hacer "bien social". Ella considera la ética tecnológica como el trabajo de su generación. Ella ya sabe que los programadores de computadoras necesitan aprender a hacer algoritmos menos sesgados, y sabe que esto requerirá que las compañías tecnológicas y el público exijan justicia y ética. Ella quiere ayudar a abordar la desigualdad, y es muy consciente de la ironía de que su excelente educación es la encarnación misma de la desigualdad.

Después de todo, nuestra infraestructura social permite, incluso porristas, que ciertas personas aprendan mucho más que otras. No es noticia que esas mismas personas estén preparadas para dominar el futuro. Sin embargo, lo que es notable es el surgimiento de una clase de personas que no solo están posicionadas para dar forma al futuro de la economía de acuerdo con su voluntad, sino que simultáneamente creen que sus propios esfuerzos serán necesarios y suficientes para corregir las injusticias de esa desigualdad. futuro.

Los estudiantes y ex alumnos de instituciones de élite como Exeter, o MIT y Harvard (donde sirvo como capellán) generalmente están capacitados para vernos como ciudadanos generosos, atentos y preocupados. No somos ignorantes o insensibles al sufrimiento de otros que son menos afortunados, nos decimos. Por el contrario, todo se trata de "servicio". Seguramente ayudaremos a otros si, cuando, tenemos éxito. En realidad, es importante que tengamos el mayor éxito posible; solo entonces tendremos los recursos necesarios para ayudar.

Y, sin embargo, otra narrativa dice, también somos el mejor. Somos especiales, excepcionales, dotados. Aspiramos a la inclusión. Pero también todavía nos enseñan: se agresivo. Sal y ganar. Aprovecha cada oportunidad.

¿Qué pasa si solo podemos tener una cara de la moneda?

Los estudiantes ganadores que se llevan todo

Anand Giridharadas (Foto de Matt Winkelmeyer / Getty Images para WIRED25)

En su libro Los ganadores se llevan todoescritor Anand Giridharadas critica lo que él llama la religión del "win-winism": la creencia de que las personas cuya dominación cada vez mayor de nuestro mundo social, económico y político no solo son capaces de solucionar los problemas de desigualdad e injusticia que causa su dominación, sino que de hecho están en una posición ideal, en virtud de sus victorias, para sean salvadores y liberadores de los que han perdido.

Por lo tanto, Mark Zuckerberg defiende la libertad de expresión como una creencia democrática central y al mismo tiempo socava la democracia al tomar millones para publicar anuncios políticos falsos. O tienes a Marc Benioff proclamando el fin del capitalismo y una nueva era de ética mientras manteniendo su propio estado multimillonario y defender el apoyo de Salesforce a ICE, incluso cuando los niños indocumentados están separados de sus familias.

Mientras hablamos en un MIT Media Lab En la sala de conferencias, la madre de Gupta, nacida en China, que llegó a Estados Unidos justo después de graduarse de la escuela después de que las protestas dirigidas por estudiantes sacudieron la Plaza Tiananmen de Beijing, observa con orgullo la evidente excelencia de su hija.

Sin embargo, ¿cómo será la experiencia posterior a la universidad para alguien que desarrolló habilidades técnicas e interpersonales como la de Gupta cuando era adolescente? Después de quince años en Harvard y el MIT, puedo decirte que la gente le dará trabajo y dinero. Quiero decir, nunca se sabe quién terminará siendo multimillonario, pero es poco probable que termine durmiendo en su automóvil.

O bien, no hagamos esto con Gupta, a quien realmente me gusta y deseo bien. La pregunta más importante es: ¿Será el futuro del trabajo una distopía en la que los jóvenes reflexivos como Gupta se digan a sí mismos que quieren salvar el mundo, pero terminen decisión el mundo en su lugar? ¿O pueden los estudiantes que ahora asisten a escuelas privadas de élite y universidades y conferencias en el MIT usar su destreza con las herramientas del maestro para desmantelar su propia casa?

Un capellán no religioso

Sin embargo, retroceder, podría ayudar a explicar cómo un capellán no religioso incluso se involucró en tecnología y el futuro del trabajo en primer lugar.

Yo era un estudiante de religión en la universidad que pensaba en ser un sacerdote budista o taoísta, pero finalmente me ordené como rabino y me convertí en clérigo de los no religiosos (he sido capellán humanista en la Universidad de Harvard desde 2005).

Hace una década, escribí un libro llamado Bueno sin dios, sobre cómo millones de personas viven vidas buenas, éticas y significativas sin religión. Aun así, sostuve que las personas no religiosas deberían aprender de las formas en que las comunidades religiosas construyen congregaciones para generar apoyo e inspiración mutuos. Discutí públicamente con otros ateos como Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris y Lawrence Krauss por su agresiva condena de todos los aspectos de la religión, incluso las partes que inspiran a los trabajadores que no han tenido la extraordinaria fortuna de ser tan educados como ellos. Y, tratando de concentrarme en lo positivo en lugar de simplemente decirles a los demás qué no hacer, cofundé y dirigí (hasta que cerró el año pasado) una de las "congregaciones impías" más grandes del mundo.

"Bien sin Dios" por el autor.

¿Suena completamente ajeno a todo lo que viniste a leer a este sitio? Si es así, tienes razón, y ese es el punto. Hasta hace poco, nunca había estado involucrado en la tecnología como algo más que un consumidor entusiasta y, a veces, adicto.

La ética de la tecnología

Las cosas comenzaron a evolucionar a principios de 2018, cuando me uní a la Oficina de Vida Religiosa del MIT (que pronto cambió su nombre a la Oficina de Vida Religiosa, Espiritual y Ética u ORSEL) como Capellán Humanista. La oficina también me colocó en un nuevo rol llamado "Convener" para "Vida ética", pidiéndome en otras palabras que convocara a personas en todo el campus para reflexionar sobre cómo vivir una vida ética desde una perspectiva secular. Resulta que la ética no religiosa es importante en un campus de alta tecnología como el MIT, una institución tan secular que solo alrededor del 49 por ciento de sus estudiantes se consideran religiosos.

En el pasado, podría haber rechazado la oferta del MIT (mis responsabilidades en Harvard y en otros lugares me mantuvieron lo suficientemente ocupado, muchas gracias). Pero, si soy sincero, cuando me pidieron que me uniera, estaba pasando por mi propia crisis de conciencia. Había comenzado a cuestionar seriamente mi propia visión ética.

No, No había encontrado a Dios (muy gracioso). yo tenía, Sin embargo, descubrí algunos defectos serios en los valores con los que crecí como un hombre blanco relativamente privilegiado, heterosexual y de género cis que creía en el poder y la virtud del capitalismo estadounidense. Eso es relativamente privilegiado, por cierto: mi madre era una niña refugiada que vino a los Estados Unidos desde Cuba sin nada. Mis padres asistieron a la universidad comunitaria, mi padre nunca se graduó y el único dinero que obtuve de él después de su muerte cuando yo era adolescente provenía de sus cheques del Seguro Social.

Sin embargo, ahora me doy cuenta de que logré crecer, hacer siete años de estudios de posgrado y comenzar una carrera decentemente prominente en torno a la "ética" sin reconocer plenamente qué parte de la cultura estadounidense y la civilización occidental es fundamentalmente injusta.

Leyendo Coates Ta-Nehisi' libro Entre el mundo y yo en 2015, comencé a pensar en cómo la esclavitud no solo era el mal moral que siempre había considerado, sino que era el soltero. más grande industria. en las décadas fundacionales de la historia estadounidense. Como el Revista del New York Times "Proyecto 1619"Demostrado, el excepcionalismo político y económico de este país, que abracé como hijo de un refugiado de un régimen comunista brutal, fue construido en su totalidad sobre una base de brutal opresión y explotación.

"Entre el mundo y yo" por Ta-Nehisi Coates

Con la elección de Donald Trump, ya no pude evitar la conclusión de que la supremacía blanca y la cleptocracia están vivas y bien, aquí y ahora. Luego vinieron #YesAllWomen y #MeToo. Aunque fui criada como una orgullosa feminista, me encontré reflexionando sobre algunas de las formas nocivas en las que me habían enseñado a ser hombre. Nunca admita vulnerabilidad, excepto tal vez en privado y avergonzado, a una mujer en la que confiaba demasiado para obtener apoyo emocional. Ser agresivo. Siempre gana, porque los perdedores son las cosas más valiosas y miserables en la tierra.

Como millones de personas, pasé mi vida bajo el control de una cierta tensión de la meritocracia estadounidense que predica un dogma relativamente secular pero fantástico: que las personas como yo son ganadores talentosos y talentosos que deberían dedicar la mayor parte de nuestra energía en la vida a logrando tanto éxito personal como sea humanamente posible. ¿Y si toda nuestra victoria y dominio alguna vez comienza a parecer injusto, incluso un poco cruel u opresivo? Sin preocupaciones. Lo justificaremos todo "devolviendo", a través del servicio comunitario o la filantropía o ambos.

Ese es el nivel de cinismo y dudas que estaba experimentando cuando llegué al MIT el año pasado. Entonces, uno de mis alumnos señaló: "si todas las compañías que comenzaran con los alumnos del MIT se combinaran en un país, sería en el G20". La mayor parte de mi vida, habría tomado su comentario como un motivo de orgullo. En cambio, comencé a darme cuenta: tal vez lugares como este son el problema, simplemente al acumular tanta riqueza y poder del mundo que miles de millones de personas se quedan prácticamente sin ninguno.

Tal vez las personas como yo, orgullosas y demasiado poco críticas dedicándonos a servir a estos lugares, son el problema.

En resumen, tal vez Soy el problema.

Entra Giridharadas, el crítico del capitalismo contemporáneo, cuyo trabajo me fue presentado el año pasado por un estudiante de la Harvard Business School. Cuando Los ganadores se llevan todo salió el otoño pasado, había estudiantes jadeando mientras lo leían en los pasillos de HBS antes de las vacaciones. Giridharadas, un estadounidense de 38 años que habla rápido, tiene un vestuario completamente negro y una capacidad sobrenatural para volverse viral en Twitter, argumenta que "vivimos en una era de desigualdad asombrosa que se trata fundamentalmente de monopolizar el futuro mismo". "Como me dijo para mi primera columna TechCrunch en marzo.

"Los ganadores de nuestra época, las personas que logran estar en el lado correcto de una era de cambios precipitados y abandono, han logrado construir, operar y mantener sistemas que les extraen la mayoría de los frutos del progreso". continuado. Un verdadero iconoclasta, Giridharadas no se disculpa por completo al criticar a los héroes más grandes de la generación pasada: titanes de negocios y filántropos como Zuckerberg y Bill Gates quienes regalan miles de millones pero, argumenta, lo hacen principalmente para ocultar la codicia, la explotación y la subversión de la democracia.

A través de sus palabras, me vi a mí mismo y al status quo que había ayudado a mantener al no criticar las estructuras en las que existía, y me sentí avergonzado. Pero a diferencia de la vergüenza que sentí cuando era joven al interiorizar la masculinidad tóxica, no quería ocultar mis sentimientos, reprimirlos o confesarlos solo a mi esposa. Quería poseerlos públicamente y hacer algo al respecto.

Durante este mismo tiempo, me aclimaté en el MIT y me sentí casi obsesivamente atraído por la lectura sobre "la ética de la tecnología", un tema emergente pero campo de estudio amorfo en el que académicos, activistas, formuladores de políticas, líderes empresariales y otros debaten las ramificaciones sociales del cambio tecnológico.

La tecnología, después de todo, se ha convertido en la máxima religión secular. ¿Qué más da forma a los valores de hoy? (¡la innovación siempre es buena!); requiere rituales diarios (en la antigüedad, rezábamos cuando nos despertábamos, cuando nos dormíamos, y durante cada día; eso ahora se llama, "revisar nuestros teléfonos"); ofrece abundantes profetas (VC's, TED Talkers y lo que el escritor del New York Times Mike Isaac llama acertadamente "El Culto del Fundador"); y tal vez incluso deidades (como en el héroe tecnológico semi deshonrado Anthony Levandowski intento aparentemente sincero de fundar una iglesia adorando al dios de la IA del futuro)?

Si pensamos en la tecnología como una religión o una "industria" (aunque qué industria no es ¿basado en tecnología hoy?), claramente está causando un terrible sufrimiento y división. Uber y Lyft moviliza a millones de conductores en todo el mundo, y quizás la mayoría gana salarios de pobreza. Plataformas como YouTube y Facebook "democratizan" la cultura, permitiendo a miles de millones publicar sus opiniones. Para hacerlo, diseñan algoritmos tan intencionalmente adictivos e inflamatorios, que el mundo parece haber perdido gran parte de la capacidad que tenía en el proceso de llevar a cabo elecciones libres y justas que privan a las minorías y los trabajadores. Y los centros de datos gigantes que impulsan toda esta IA que “cambia el mundo” son peor para el clima que cientos de vuelos transatlánticos. Podría seguir.

Así que comencé una columna en TechCrunch y tomé un año sabático para estudiar la ética de la tecnología, de la cual "el futuro del trabajo" es parte. Lo que nos lleva a este verano.

Sintiéndome como un estudiante de MIT ansioso y ansioso, me dirijo a EmTech Next con mi pase de prensa y mi primer trabajo como reportero. Estoy anticipando un trabajo jugoso, investigando las posturas éticas de las empresas y los oradores que estarán disponibles en la conferencia.

Al caminar, sin embargo, me doy cuenta de que estoy atrapado en una pregunta más básica. ¿Qué significa exactamente la frase "el futuro del trabajo"?

Que incluso es "¿El futuro del trabajo?

La última década ha traído una explosión en libros, artículos, comisiones, convenciones, cursos y expertos que afirman ayudar a determinar "El futuro del trabajo". Los autores influyentes 'FoW' han dirigido centros de estudios y universidades, abogando por los discapacitados y desfavorecidos , aconsejó a los padres acosados, e incluso se postuló para un cargo político importante. A principios de este año, el gobernador de California Gavin Newsom incluso anunció un prestigioso "Comisión del Futuro del Trabajo", El primero de su tipo en servir en una capacidad de todo el estado.

En los círculos de ética tecnológica, la frase hace referencia a un subgénero crucial en el que algunos de los debates de política más feroces de nuestro tiempo: ¿son los empleos que las empresas tecnológicas crean realmente buenos para la sociedad? ¿Qué haremos si / cuando los roben? ¿Y cómo cambiar nuestro trabajo también cambia la forma en que pensamos sobre nuestras vidas y nuestra propia humanidad?

La frase se remonta a más de un siglo, tal vez acuñada por el irónicamente teórico económico británico-italiano L.G. Chiozza Money, quien argumentó en "El futuro del trabajo y otros ensayos", que la ciencia ya había resuelto "el problema de la pobreza", si tan solo la humanidad pudiera superar la desorganización y el desperdicio que caracteriza al capitalismo competitivo en ese momento (!).

Más recientemente, un HORA La historia de portada sobre "El futuro del trabajo" de hace una década ayudó a popularizar lo que solemos decir con la frase de hoy. "Hace diez años", comenzó, "Facebook no existía. Diez años antes de eso, no teníamos la Web ". El subtítulo preguntó:" ¿Quién sabe qué trabajos nacerán dentro de una década? "

Portada de "El futuro del trabajo" de Time (25 de mayo de 2009).

Conveniente, porque por supuesto ahora sabemos exactamente qué trabajos han nacido.

La historia de TIME presentaba diez predicciones: la tecnología superaría a las finanzas como el principal empleador de las élites; horarios flexibles y aumento del liderazgo de las mujeres; oficinas tradicionales y beneficios en declive. No es que los reclamos resultaron ser atroces; pero cuando pronostica tendencias generales, el valor radica en cuestiones de matices, como "¿en qué medida?" Seguro, las mujeres obtuvieron ganancias durante la década, pero ¿quién diría que lo hicieron? en un grado aceptable?

Algunos libros FoW más matizados, como La segunda era de la máquina, por los profesores del MIT Erik Brynjolffson y Andrew McAfee, adoptan una perspectiva optimista sobre la tecnología: esas "máquinas brillantes" pronto ayudarán a crear un mundo de progreso abundante, ejemplificado por el éxito de Instagram y los multimillonarios que creó la compañía y su modelo de negocio. Pero Brynjolffson y McAfee comparan Instagram con Kodak, sin ofrecer soluciones al problema de que Kodak alguna vez empleó a 145,000 personas en trabajos de clase media, en comparación con unos pocos miles de trabajadores en Instagram.

"La segunda era de la máquina" por Erik Brynjolffson y Andrew McAfee

Llegaría a preguntarme si filosofar sobre "el futuro del trabajo" es solo una forma en que las personas más ricas e influyentes del mundo se convencen de que se preocupan profundamente por sus empleados, cuando lo que hacen es más como diseñar estrategias para continuar ser exorbitantemente poderoso en las próximas décadas?

"Trayectorias divergentes", otros eufemismos y humanismo multimillonario

Bueno, sí.

Un nuevo y elegante informe del McKinsey Global Institute, "El futuro del trabajo en los Estados Unidos", Enfatiza" trayectorias divergentes "," diferentes puntos de partida "," brechas cada vez mayores ", la" concentración "de crecimiento y otros eufemismos para aumentar la desigualdad que casi seguramente caracterizarán el futuro cercano del trabajo, alimentando la creciente ira y polarización. Su punto es bastante claro: una mayor polarización significa que ciertos sectores como la salud y STEM están preparados para grandes ganancias. Otros campos como el soporte de oficina, la producción manufacturera y los trabajos de servicio de alimentos podrían verse afectados.

La "Comisión de Cambio", una iniciativa financiada por ahora probable candidato presidencial Michael Bloomberg, producido otro influyente informe del Futuro del Trabajo en 2017. En el informe Shift, la organización de Bloomberg, en asociación con el centro de estudios centrista New America, enfatiza más trabajo futuro para las personas mayores, la preocupación por los trabajos en lugares que han sido "dejados atrás" y la preocupación general de que el dinamismo económico del país podría lento.

Michael Bloomberg (Foto por Yana Paskova / Getty Images)

El informe describe cuatro escenarios bajo los cuales el trabajo en Estados Unidos podría cambiar en 10-20 años. ¿Habrá más o menos trabajo, y ese trabajo será principalmente "trabajos" en el sentido tradicional o "tareas" en el sentido de proyectos, conciertos, trabajo independiente, trabajo a pedido, etc.? Cada escenario lleva el nombre de un juego: Rock Paper Scissors, King of the Castle, Jump Rope y Go. Lo que me recuerda un cierto meme de Twitter:

Absolutamente nadie:

Nadie:

Literalmente ninguna persona:

La Comisión de Cambio: "¡Hey, hagamos nuestras deliberaciones sobre si las personas podrán encontrar trabajos decentes dentro de una generación, o si casi todos menos nosotros terminaremos en la pobreza, en un juego cursi!"

Claro, parte de la estrategia "ganadora" para hacer negocios con éxito siempre ha sido divertirse un poco, y hacer un poco de bien, mientras se establecen las reglas de la competencia en gran medida a su favor. ¿Pero los diferentes resultados posibles del futuro del trabajo serán percibidos como "diversión y juegos" tanto por los perdedores de esos juegos como por los vencedores?

El informe de Shift, escribió Bloomberg, tenía como objetivo "eliminar la hipérbole y el tono del fin del mundo que tan a menudo caracterizan la discusión sobre (el futuro del trabajo"), pero el tono y el contenido del informe tienen sus propios problemas.

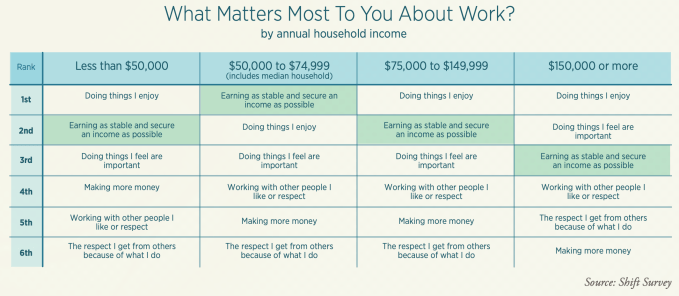

Los organizadores destacan una encuesta que encuentra que “solo las personas que ganan $ 150,000 al año o más dicen que valoran hacer un trabajo que es importante para ellos. Todos los demás priorizan un ingreso estable y seguro ”. ¿La base para esta conclusión? Dadas varias opciones para clasificar en términos de "¿Qué es lo que más te importa del trabajo?", Solo el grupo de ingresos más altos eligió "hacer las cosas que considero importantes" en lugar de "obtener un ingreso lo más estable y seguro posible".

Pero si las personas tienen tanto miedo de caer en la indigencia que priorizarán la seguridad sobre el significado, eso no significa que de repente descubrimos algo de Gran Verdad acerca de cómo solo a las personas ricas les gustaría llevar vidas significativas.

Via Shift Informe de la Comisión sobre el futuro del trabajo

También, todos los escenarios de Shift / Bloomberg me parecen distópicos hasta cierto punto: todos parecen profetizar la creciente adicción a la pantalla y la competencia por el trabajo entre todos, pero una élite ultra rica y educada que continúa ganando poder sin importar qué "juego" se convierta en realidad. Ninguna de las opciones es un futuro más regulado, menos desigual, dramáticamente más equitativo.

Lo que me hace pensar que todos los diversos escenarios explorados en Shift, McKinsey y otros informes son solo … escenarios, como cuando los presentadores de programas de entrevistas con gruesos acentos de Brooklyn o Bahstán analizan quién es seguro va a ganar el Super Bowl del año próximo o las Finales de la NBA.

Ahora, confieso: en lugar de descargar el último podcast de cadera de El neoyorquino o Pineapple Street Media o donde sea, en mi tiempo libre, como lo he hecho desde que era un niño, y como muchos hombres, escucho a otros hombres sentados en busca de engendros: adivinando las líneas de apuestas, prediciendo los ganadores y perdedores, los MVP y las cabras

Es un pasatiempo terrible, pero básicamente soy adicto, aunque felizmente no en el juego deportivo que suscribe muchos de mis programas de entrevistas deportivos favoritos. Yo no juego, pero entiendo el atractivo de apostar en juegos, jugadores y resultados. Y no necesita ser un corredor de apuestas en Las Vegas para comprender por qué tantos hombres como yo pasan nuestro tiempo de esta manera: Queremos saber qué pasará. Queremos ser profetas. Queremos tener el control. Queremos justicia poética. Pero no tenemos una forma realista de obtener nada de eso, así que nos sumergimos en una especie de ritual religioso para convencernos de que tenemos el control. Una ilusión diaria, una forma de alquimia, una pseudociencia.

¿VC es lo mismo? ¿Hay mucho periodismo tecnológico? ¿E incluso un poco de lo que pasa por la ética tecnológica?

No lo se, pero yo hacer Sabemos que al abordar si sus diversos escenarios del Futuro del Trabajo arrojarán predicciones precisas, los organizadores de la Comisión de Cambio ofrecen una respuesta típica de FoW. Citan la declaración de John Kenneth Galbraith de que "tenemos dos clases de pronosticadores: los que no saben y los que no saben no saben".

Quizás lo que subraya todo esto es que cualquier esperanza que la mayoría de nosotros tenga para un futuro benigno de trabajo se proyecta cada vez más en lo que he llegado a considerar como "humanismo multimillonario".

El humanismo multimillonario es lo que sucede cuando decir Valoramos cada vida humana como primitiva e igualitaria, pero en la práctica estamos bien si la mayoría de los humanos sufren bajo el estrés de todo tipo de precariedad, desde el nacimiento hasta la muerte, para que un puñado de humanos pueda vivir vidas de extraordinaria libertad y lujo.

El humanismo multimillonario es un mundo en el que, como Ghiridaradas me señaló para TechCrunch, inventamos todo tipo de cosas nuevas y, sin embargo, la esperanza de vida disminuye, la alfabetización disminuye y la salud y el bienestar en general disminuyen. El humanismo multimillonario es cuando experimentamos eso como nuestra realidad diaria, pero se espera que estemos agradecidos por el "progreso", como si el estado actual de las cosas fuera el mejor de todos los mundos posibles y el futuro seguramente también lo sea. Es por eso es apropiado estar enojado cuando contemplamos estas preguntas.

Lo que me lleva de vuelta a Gupta. Cuando hablé con ella en el MIT, estaba muy consciente de que ella Era el futuro del trabajo. Para una estudiante de secundaria (o incluso si tenía veintitantos años), muestra una conciencia e interés tan impresionantes en los problemas éticos en la IA y la formulación de políticas ambientales.

Pero cuando le pregunto qué quiere obtener de asistir a EmTech Next, ella responde: “Esperaba aprender algo sobre lo que podría querer estudiar en la universidad. Después de eso, ¿qué tipo de trabajos quiero perseguir que vayan a existir y tengan demanda y sean realmente interesantes, que tengan un impacto en otras personas?

En otras palabras, comprensiblemente, Gupta también parece querer saber el futuro para poder controlarlo. ¿Pero es la idea de conseguir un trabajo que sea muy solicitado e interesante? ¿O uno que tenga un "impacto"? Claro, uno puede soñar con ambos, pero ¿qué pasa si uno necesita elegir más de uno sobre el otro? Hay una ambivalencia fundamental en su respuesta: una especie de agnosticismo, una cobertura de las apuestas, un "depende".

Y si "depende" es a lo que finalmente se reduce el estudio y las conferencias sobre el futuro del trabajo, entonces no debería considerarse como el tipo de empresa "importante" que la cohorte más rica en el estudio de la Comisión de Turnos dijo que valoraba mucho.

¿Qué clase de futuro y para quién?

David Autor a través de MIT Technology Review

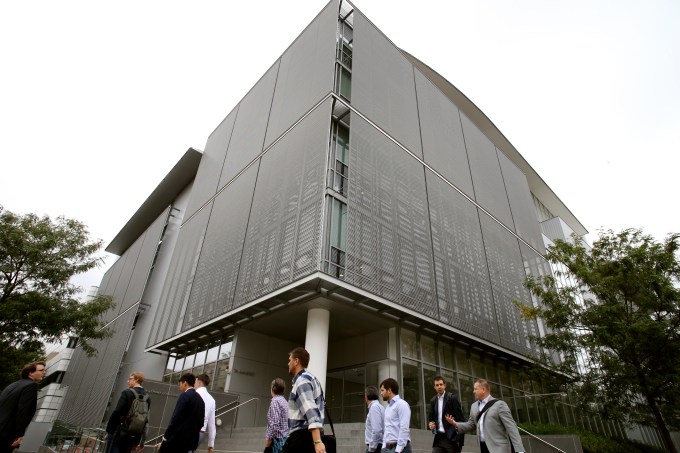

Cuando comienza la conferencia EmTech Next, soy tan ambivalente como siempre. Estamos en el auditorio en el último piso del más nuevo de los dos edificios para el Laboratorio de Medios del MIT (la famosa "futura fábrica" como es ampliamente conocida). El edificio del Laboratorio de Medios es una exhibición tan impresionante de diseño moderno y robots experimentales en progreso que se asoman desde detrás de las paredes de vidrio del laboratorio que se extienden hasta los techos de las catedrales que incluso una niña preadolescente vestida a la moda deambula por los pasillos con su padre, un cabello desordenado trabajador aquí, se puede escuchar diciendo: "Yo amor tu trabajo. Sus asi que guay aquí dentro …

El orador de apertura de la conferencia, el profesor de economía del MIT David Autor, presenta en su último artículo, "Obra del pasado, obra del futuro". Autor estudia a los trabajadores desplazados: sin educación universitaria, en su mayoría hombres de manufactura que han soportado lo que él llama los" choques "de la automatización. Estos trabajadores alguna vez pudieron ganar salarios superiores en las grandes ciudades, lo que mitigó la desigualdad tóxica, pero ya no, explica Autor. Con la mayoría de estos trabajos automatizados fuera de existencia o externalizados a otros países, las grandes ciudades se han convertido en refugios concentrados de oportunidades para personas más ricas, más jóvenes, más saludables y altamente educadas.

La charla del autor se centra en "reconstruir las carreras profesionales" para los menos educados, lo que sería enormemente estimulante, dice, para nuestro sentido de prosperidad compartida.

Eso es indiscutible, pero mirando a través de mi lente Giridharadas, me pregunto, ¿el futuro del trabajo, como lo imaginan economistas como Autor, implicará una división enorme e interminable entre los que tienen y los que no tienen? ¿Son las soluciones de tirita a la desigualdad impulsada por el mercado lo mejor que podemos esperar? (Bien, quizás Autor está proponiendo una cirugía menor, pero en una herida abierta y cancerosa).

En el vacío, parece atractivo dar a los trabajadores más pobres más "capacitación", más "conjuntos de habilidades refinadas". Pero tales ideas tienden a absorber cualquier ancho de banda que las personas ocupadas en reuniones como EmTech Next están dispuestas a dedicar a pensar en problemas sociales. Así que nos sentimos bien con nuestra magnanimidad durante un par de horas, luego continuamos ganando en un grado obsceno, en lugar de abordar de manera sustancial la explotación salvaje, el racismo y la codicia en el corazón de por qué las personas son pobres en primer lugar.

El panel de apertura se vuelve particularmente deprimente cuando se dirige al co-panelista de Autor Paul Osterman, profesor de gestión de recursos humanos en la escuela de negocios Sloan del MIT. El libro de Osterman ¿Quién cuidará de nosotros? y sus comentarios aquí son sobre la mejora de las condiciones para los millones de "trabajadores de atención directa" (como enfermeras y auxiliares) que atenderán a los estadounidenses mayores en los próximos años. Necesitamos más y mejores opciones de capacitación para dichos trabajadores, dice Osterman.

¡Bastante seguro! ¿Pero es ESA la gran idea para el futuro del trabajo? ¿Mejorar las oportunidades de limpieza después de que personas ricas como las que asisten a esta conferencia, cuando nos hacemos demasiado viejos o enfermos para limpiar nuestros propios cuerpos? Mientras escribo esto, pienso en mi padre, que creció pobre, nunca terminó la universidad y se esforzó pero nunca se "graduó" a una clase social más alta. "Tenía sabor a champán y un presupuesto de agua", su hermana una vez me contó sobre él muchos años después de su muerte.

En las últimas semanas de su vida, durante mi último año de escuela secundaria, papá a veces necesitaba mi ayuda para llevar su cuerpo demacrado y afectado por el cáncer al inodoro. El estrés y la tristeza de esa experiencia se quedaron conmigo de por vida; Tengo un gran respeto por las personas que realizan un trabajo de cuidado profesionalmente todos los días. Pero es irritante escuchar una sala llena de jefes asintiendo: no solo millones de personas más pobres deben hacer ese trabajo, sino que también es una gran oportunidad para ellos. Deberían estar agradecidos de que planeemos su futuro de manera tan brillante y reflexiva.

Y eso es lo que economistas como Autor y Osterman, junto con todo un género de pensadores similares, me parece que estoy diciendo: que "nosotros" los pocos ingeniosos que controlan el dinero y la política están aquí para decidir el destino de "ellos", Las personas más pobres que no tienen la suerte de estar hoy en la habitación con nosotros. Por supuesto, aliviemos el sufrimiento de las personas y "devolvamos" a ellos.

¿Pero tenemos la responsabilidad de traerlos a la sala con nosotros para tomar decisiones como iguales?

La economía del cambio real y estructural.

El espíritu del "futuro del trabajo" puede ser una tarifa perfectamente estándar para el tipo de perspectiva económicamente centrista a la que solía suscribirme y que ha caracterizado a la mayoría del liderazgo del partido demócrata estadounidense desde el ascenso de Bill Clinton. But it doesn’t represent what Elizabeth Warren has taken to calling “Big, Structural Change,” or what Bernie Sanders, hands akimbo, white hair and spittle flying, calls, “Revuhlooshun!”

Yes, let’s talk about how to pay health aides and construction workers a little better and how to “give back,” but by no means should we upend our economy to pay reparations, or tell the global rich to “take less,” as Giridharadas demands in his writing.

I talked with Autor just after the conference, and I admit part of me wanted him to make things simple by being a bad guy: sympathetic to the rich, condescending to the poor, a neoliberal hack making techies feel good about themselves by proposing partial solutions that don’t challenge power or privilege. It’s hard to pin him that way, though, and not just because he’s been wearing a gecko earring since he bought it in Berkeley with his wife decades ago.

Yes, Autor told me, he is a capitalist believer in market economies. Yes, labor unions have bashed his work at times, in a “knee-jerk” way he finds “super irritating.” But he sees improved dialogue of late, now that he’s come to believe organized labor needs a larger role in society. And labor leaders have “accepted that the world’s changed,” Autor says, "not just because of mean bosses and politicians … there are underlying economic forces that impact the work people do.”

Autor is also a Jewish liberal who spent three years worth of his own work time teaching computer skills to poor, mostly Black people as an early employee of GLIDE, a large United Methodist church in San Francisco’s Tenderloin district now famous for its 100-member gospel choir, LGBT-affirming attitude, and a community clinic serving thousands of homeless people each year from the church’s extensive basement. That’s not nothing.

The GLIDE Ensemble performs during a Celebration of Life Service held for the late San Francisco Mayor Ed Lee on December 17, 2017 in San Francisco, California. (Photo by Justin Sullivan/Getty Images)

“I met twice with President Obama,” Autor proudly volunteers. So I figure I’ll ask him about Senator Warren, a prominent Presidential aspirant who literally lives in our neighborhood, and who is building her message around economic justice. Autor has also met with her. He likes her approach to antitrust regulation and consumer protection. But her proposal to pay off student loans is “dumb,” he says, because it will transfer too much money to the rich.

But is that our biggest concern when trying to make inclusive economic policy? All the rich people who are apparently taking out student loans?

Of course, my questions about Autor and Osterman are really about practically the entire field of economics. For generations, economists have asked us to take on faith that their unique genius can calibrate our financial system to advance prosperity and avoid collective ruin. But what about using that same genius to make the system itself more just and equal?

That, they say, is beyond their (or anyone’s) powers.

“Economics really is a branch of moral theology,” said the great tech critic Neil Postman, in promoting his 1992 book Technopoly, about how technology had (already!) become a religion and that America was becoming the first nation to adopt it as its official State Spirituality. “It should be taught more in divinity schools than in universities.”

What about Universal Basic Income?

Supporters of Democratic presidential candidate, entrepreneur Andrew Yang march outside of the Wells Fargo Arena before the start of the Liberty and Justice Celebration on November 01, 2019 in Des Moines, Iowa. (Photo by Scott Olson/Getty Images)

Martin Ford’s book The Rise of the Robots looks at the future of work less optimistically, lamenting that new industries will “rarely, if ever, be highly labor-intensive,” and ultimately calling for a Universal Basic Income (UBI) — a favorite solution of many tech leaders and future-of-work analysts alike, including Andrew Yang, the tech entrepreneur and unlikely top-tier Democratic presidential candidate.

Yang’s rise in popularity owes much to his identification with the tech community, including support from icons like Elon Musk. And in referring to his own prescribed version of UBI as the “Freedom Dividend,” Yang nods not only to ‘freedom,’ long a staple of presidential rhetoric on left and right, but also to the ‘dividends’ paid by companies to shareholders. At a time when some politicians propose ending capitalism as we know it, Yang’s language suggests remaking America in Big Tech’s image.

It’s tempting, for obvious reasons, to envision monthly thousand-dollar checks for millions of struggling Americans. Yet for all its fanfare, UBI does essentially nothing to address the metastasizing cancer of structural inequality in American society. Under the “freedom dividend,” the poor remain poor, while the rich almost certainly continue an inexorable upward march toward ever greater wealth. All of this would be essentially by design.

Think about the staggering inequality tech entrepreneurs have already overseen in and around Silicon Valley: homelessness, gentrification, and wage stagnation for all but the rich. That funneling of money to the wealthiest is not a bug in tech’s code. Economic exploitation was a core feature of Silicon Valley back in the 70’s and 80’s. It remains a core feature today.

The Freedom Dividend, in practice, will involve most Americans scraping by on (maybe!) a thousand more dollars a month, while elites gain ever firmer control over the entire world around them. That’s not identifying and creating structural change in the future of work.

A maddening feedback loop: the problem with “mission-driven” work

Karen Hao via MIT Technology Review

After the Autor and Osterman panels, I head out to interview Karen Hao, the AI reporter for the MIT Technology Review. Less than a decade out of her undergraduate degree at MIT, Hao writes mainly on the ethical implications of AI technologies and their impact on society, both in thoughtful articles and a snappy email newsletter, the Algorithm. Her sources and inspiration for stories are often her former dormmates and classmates.

She gravitated towards ethics stories because of a brief stint she’d had working at her dream job: a mission-driven tech company, at which, she told me, the founder and CEO was ousted by the board within months of Hao’s arrival, “because it was también mission driven and wasn’t making any profit.”

“That was a pretty big shakeup for me,” Hao said, “in realizing I don’t think I’m cut out to work in the private sector, because I am a very mission-driven person. It is not palatable for me to be working at a place that has to scale down their ambition or pivot their mission because of financial reasons.”

Hao’s comments got me thinking about the larger systems in which all of us who live and work in technology’s orbit seem to be trapped. We want to do good, but we also want to live well. Few of us imagine ourselves among the class that ought to intentionally step backward socio-economically so others might step forward. After all, there are tech executives who make $400,000 a year but still can’t afford their mortgages in Silicon Valley: should the revolution begin with them? But if not, just who hace need to take personal responsibility for participating in oppressive systems of privilege?

Whatever the answers, Hao strikes me as sincere, smart, and well-intentioned, and I’m impressed she gravitated away from the moral compromise of the for-profit sector to her current role as a journalist, toward “mission-driven” work. But now that I’m not sitting with her as her chaplain but as a fellow journalist, should I dig deeper, question harder?

los MIT Technology Review, after all, might have something to gain from presenting a certain kind of tech coverage. There are advertising dollars and conference registration fees at stake, and it’s not difficult to imagine how these things might incentivize coverage that pulls punches. Attendees at a conference like EmTech Next might want to be challenged intellectually to think about ethics. But do they really want to hear, for two days straight, about perspectives that would cause them to question not only their own money-making abilities but also their moral character?

Granted, these are the risks one runs in trusting the coverage of virtually any issue at virtually any mass-media publication. And particularly after the despicable and anti-American treatment to which Donald Trump has subjected the press these past few years, I tend to give hard-working journalists such as Hao the benefit of the doubt. That said, how many costly errors in judgment at tech companies could have been avoided if tech coverage had been less fawning?

And one need only look down the road a few … actually not even a few steps from where Hao and I are sitting, to realize that sometimes even the most promising-seeming efforts to write about and study technology ethically are deeply flawed at best.

The exterior of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Media Lab/ (Photo by Craig F. Walker/The Boston Globe via Getty Images)

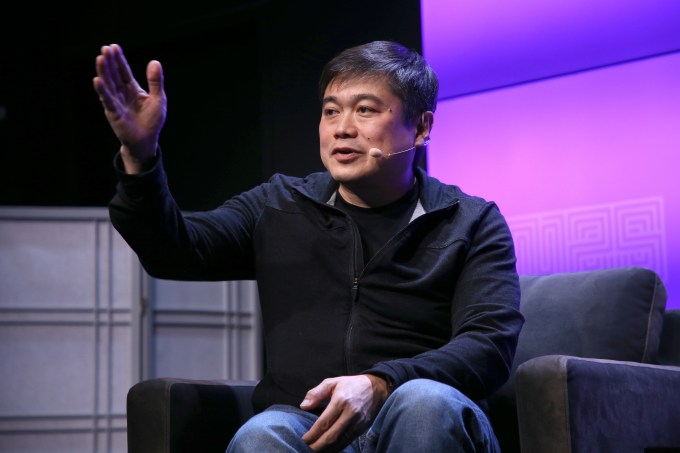

After all, the gleaming Media Lab building, in which the conference took place, was under the direction of Joi Ito, a tech ethicist so legendary that when Barack Obama took the reins of an issue of Wired magazine as a guest editor in 2016 — as the sitting United States President — he asked to personally interview Ito about the future of artificial intelligence. Just two months or so after Hao and I sat there, news broke that Ito had cultivated a longtime relationship with none other than Jeffrey Epstein (no fucking relation, thank you), the notorious child molester and a ubiquitous figure in certain elite science, tech, and writing circles.

Joi Ito (Photo by Phillip Faraone/Getty Images for WIRED25)

Not only did Ito take at least half a million dollars in donations from Epstein against the objections (and ultimately the resignations) of star Media Lab faculty, he repeatedly visited Epstein’s homes. Epstein even invested over a million dollars in funds and companies Ito personally supported. “But forgiveness,” some friends and supporters of Ito’s might say. And on a personal, human level, I see their point. I’ve never met Ito; from what I’ve heard, I assume he’s a great guy in many ways. But he used his leadership role to closely associate with a convicted criminal and known serial sex trafficker of children, who, as one MIT student wrote, was part of “a global network of powerful individuals (who) have used their influence to secure their privilege at the expense of women’s bodies and lives.”

To Ito’s credit, he seems to have been devastated by the revelation of his fundraising choices (as he should be). But had the sources of tech funding been more scrutinized by the tech media earlier, would the entire situation have been less possible?

Maybe this entire saga of Jeffrey Epstein and the Media Lab seems less than fully related to the broader point I’m trying to make about how the “future of work,” as a genre of academic discussion, refers to a vicious cycle in which a few winners perpetually win at the expense of the rest of us losers, while casting themselves not as rich jerks but generous, thoughtful moral paragons. But that’s exactly what the Epstein story is about.

Consider, for example, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, whose mission statement (at least in one iteration) states that it is “Guided by the belief that every life has equal value,” and that it “works to help all people lead healthy, productive lives.” This sounds great in theory, but what does it even mean in practice? Who decides what it looks like for every life to have “equal value?”

That last rhetorical question probably sounds pretentiously philosophical, and maybe it is. But it also has a concrete, literal answer: notwithstanding the important contributions of others like his father and wife, at the end of the day, Bill Gates decides on the direction of the foundation founded on his twelve-figure net worth.

When we think of Gates deciding how to promote the equal value of all lives, we must absolutely picture him deciding, despite the almost literal army of philanthropy consultants he would have had available to advise him otherwise, to meet cozily and honestly quite creepily with Jeffrey Epstein in 2011, long after Epstein was a convicted felon for such crimes. Where was Gates’ respect, in deciding to indulge in those meetings, for the equality and value of the lives of the girls Epstein victimized? They were vulnerable CHILDREN, as journalist Xeni Jardin points out, and Gates either knew this or willfully barrelled past a phalanx of experts who would have informed him.

Bill Gates has, to this point, escaped most criticism for his bizarre actions because of the “social good” his foundation does. And so we allow individuals like him to hoard the resources necessary to do such grand-scale charitable work. Nosotros could tax them much more and redistribute the proceeds to poor and exploited people, which might well eliminate the need for their charity in the first place. But we don’t. ¿Por qué? Largely because of the belief that people like Gates are super-geniuses, which Gates’ involvement with Epstein would seem to disprove.

Then there is MIT more broadly. The Institute’s mission statement is “to advance knowledge and educate students in science, technology, and other areas of scholarship that will best serve the nation and the world in the 21st century,” but of course, it has a long history of advancing the production of weapons of mass destruction and of serving the military-industrial complex. The university’s newly-announced Stephen A. Schwarzman College of Computing, set to be the first wing of MIT to require tech ethics coursework, is named after a donor who has close personal ties to Donald Trump, not to mention the Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, and, say, opposition to affordable housing.

It’s all a maddening feedback loop, in other words.

We continually entrust “special” individuals like Gates and Ito and institutions like MIT and Harvard with building a better future for all. We justify that trust with the myth that only they can save us from plagues to come, and then we are shocked — shocked — that they continually make decisions that seem to prioritize a better present … for themselves. Rinse. Repeat.

Of course, MIT is ultimately just a collection of people with incentives and feedback loops of their own. It supports the doing of great good as well. This is just to say that we can never afford to blindly trust tech coverage, tech ethicists, tech ethics conferences, or even tech ethics journalists slash atheist chaplains like me. There is too much money at stake, to name only one potential motivator for moral betrayal.

All of us who choose to involve ourselves with these industries, in the name of a better future, should have to live with skepticism, and prove ourselves daily through our actions.

“Show me your budget, and then I’ll tell you what your values are.”

Charles Isbell via MIT Technology Review

“There’s an old joke about organizations,” says Charles Isbell, the dean of Georgia Tech’s College of Computing and a star on the next EmTech Next panel, called ‘Responding to the Changing Nature of Work.’ “Don’t tell me what your values are, show me your budget and then I’ll tell tú what your values are. Because you spend money on the things that you care about.”

Isbell is evangelizing Georgia Tech’s online master’s program in computer science, which boasts approximately 9,000 students, an astronomical number in the context of CS, and the program also has a much higher percentage of students of color than is typical for the field. It’s the result of philosophical decisions made at the university to create an online CS master’s degree treated as completely equal to on-campus training and to admit every student who has the potential to earn a degree, rather than making any attempt at “exclusivity” by rejecting worthy candidates. Isbell projected that in the coming years all of this may lead to a situation in which up to one in eight of all people in the US who hold a graduate degree in CS will have earned it at Georgia Tech.

Tall, dapper, and with the voice and speaking style of an NPR host, Isbell draws a long line of question-askers in the hallway after his panel (including Gupta of course, and me as well). He can’t promise to even open all the emails people want to send him, so he tells those with particularly good questions to fill in the subject line with a reference to one of his favorite 80’s hip-hop records.

In a brief one-on-one interview after he finishes with his session and the line of additional questioners, I ask Isbell to explain how he and his colleagues so successfully managed to create an inclusive model of higher education in tech, when most of the trends elsewhere are in the direction of greater exclusivity. His response sums up much of what I wish the bright minds of the future of work were willing to make a bigger priority: “We have to move to a world where your prestige comes from how much better you make (your students). That means, accept every person you believe can succeed, then help them to succeed. And that’s the difference between equality and equity.”

“Equality,” Isbell continues, “is treat everyone the same, (not knowing whether) good things will obtain. Equity is about taking people who can get from here to there and putting them in a situation (to) actually succeed … without equity, you’re never going to generate the number of people we need in order to be successful, even purely from a selfish, change the economy, make the workforce stronger (point of view.)”

Maybe what we really need are conferences on the future of equity. What if the extraordinary talent, creativity, discipline, and skill that has been poured into the creation and advancement of technology these past few decades were instead applied to helping all people on earth to obtain at least a decent, free, dignified quality of life? Would we all be stuck on the iPhone 1, or even the Model T?

Perhaps, but I have to imagine if seven billion people were well-fed, educated, and cared for enough to not have to worry constantly about their basic needs, they’d have reason to collaborate and capacity to innovate.

But now I’m philosophizing for sure. So I try to snap out of it by asking a concrete and focused follow-up question of my next interviewee, MIT Technology Review’s editor-in-chief Gideon Lichfield: does Lichfield see his publication’s role as bringing about the sort of equity Isbell is describing? Or is he content for his magazine to promote the toothless, status-quo “equality” of “opportunity” most tech leaders seem to have in mind when hawking “Big Ideas” like Universal Basic Income?

Gideon Lichfield via MIT Technology Review

Once I’ve finally pulled Lichfield aside for an in-conference private audience, I find myself straining to discuss my ideas without completamente offending him. Maybe it’s his impeccably eclectic wardrobe: the European designer jacket with some sort of neon space-monster lapel pin reminds me of my childhood in New York City, trying unsuccessfully to keep up with the latest trends among kids who were either richer than me, or tougher, or both.

I don’t want to allow myself to be intimidated, but I also don’t want to sound naive about the business world he and I are both covering. And Lichfield is clearly no dummy about questions of justice and inequality; when he explains that a lot of people in his audience work at medium and large companies who have to think of the value of their investments and other “high-end decisions,” I can guess what might happen if he one day booked a conference speaker slate filled with nothing but Social Justice Warriors.

Still, I want to know how much responsibility he’s willing to take for his own role in creating a more just and equitable future of work. So I use my training as a chaplain, delivering a totally open-ended question, like we do when conducting what are called “psychosocial interviews” to figure out how a client thinks. Beyond all this talk of the future of work, I ask, “how will we know, in 20 or 30 years, that we’ve reached a better human future than the reality we have today?”

“Wow, this is tricky,” Lichfield responds. “I feel like this is a really controversial question.”

“It is,” I respond too quickly for anything but earnestness. “I’m asking you the most controversial question I can ask you.”

Lichfield eventually offers that if society’s “decision-making processes” were more accessible to poorer people, that would be a better future; because while “you could end up with disparities,” he says, “you will also end up with choice.” But does this fall short of the vision Isbell and his colleagues at Georgia Tech have expressed through their project of putting knowledge in the hands of far more people than can usually achieve it in our current system?

When I add my signature question, which I ask at the end of all of my TechCrunch interviews: “how optimistic are you about our shared human future?,” Lichfield gives me the most gloomy answer I’ve received in my over 40 interviews to date. “I’m not especially optimistic … In the very long term, you know, none of it matters. The species disappears. And I’m pretty pessimistic in the short term (as well.)”

After a brief disclaimer about how he might feel better about our prospects for the end of this century, we wrap up, and agree to chat again sometime. Yet I’m left with more ambivalence: Lichfield comes across to me as a likable guy who leads a smart and engaging publication and conference.

But how often do influential men (like me, too, at times!) use “likability” to deflect criticism, persuading you to trust their personalities instead of questioning their motives, not to mention their profits? Whether or not the point applies to Lichfield himself, it would certainly be a valid criticism of many rich executives and elite leaders who sponsor and attend conferences like this one, selling us (and themselves) on their virtue and goodness today even as they pave their own way toward even more global domination tomorrow.

The thing about ghosts is, it’s their job to haunt you

Mary Gray via MIT Technology Review

At the next big panel I attend, things turn oscuro. In a good way.

The session, entitled The Dark Side of On-Demand Work, is moderated by Hao, the AI reporter, and features Mary Gray, an anthropologist and tech researcher, and Prayag Narula, founder of the startup LeadGenius and one of the subjects of Gray’s book Ghost Work: How to Stop Silicon Valley from Building a New Global Underclass (co-authored with Siddharth Suri, a computer scientist).

“Gideon talked this morning about the best jobs and how to acquire more of them,” Hao says, quipping: “now we’ll talk about the peor jobs.”

The topic of the session is what Gray calls “on-demand platform knowledge work,” the kind of contract labor or “gig work” where the entire point is for the (now countless) people doing the labor to become invisible so as to make AI look more impressive than it currently is (not to mention so they remain in the sort of shadowy realm generally understood to be a lousy bargaining position for a living wage).

We have no exact headcount for contract labor in the U.S., but it represents most of the growth in our economy in recent years, and is expected to be a $25 billion industry by 2020.

If gig work is the future, how will workers build careers? “You don’t become an Uber driver, then a Senior Uber Driver, then an Uber Manager,” cracks Narula, who was invited to speak because his company, which he admits employs ghost workers to track down business leads for busy executives, strives to pay a living wage. In some socialist utopia off in another dimension, a Chris Rock-like comedian would crack another joke: founders talk like they should get a cookie for paying living wages, when it’s literally the least they could do.

Here in this dimension, however, living wages for ghost work are still a big deal, worthy of MIT Media Lab stages. Which is probably why Gray, whom Narula says is more “communistic” than himself, supports eliminating distinctions between full time employees and contractors, along the lines of California’s recently passed “AB5” worker law, sparking potential for a progressive gig economy revolution. Gray wants to create a “labor commons” across the country, helping people live sustainable lives; she calls her book Ghost Work “the business case” for why and how we should do it.

We love to tout AI as the future of innovation, but what if we’ve deceived ourselves, with a combination of ghost work, tax evasion, and the like, into believing our present and future societies are much more advanced than the reality?

“Not Enough Value”

Kendall Square via Tim Pierce/Wikipedia

Heading home from the conference, I’m about to get on the Red Line train at MIT’s Kendall Square station when my “Charlie Card” metro pass buzzes loudly on the card reader: “Not Enough Value.” I am so immersed in my thoughts about what technology is doing to our values, for a second I honestly read the error message as a statement about my worth as a human being.

That probably sounds like a dad joke. I love a good dad joke, but it’s not. I’ve been working for many years, in therapy and the clinical supervision I do for my work as a chaplain, on an idea that I, like a lot of smart and highly accomplished people, internalized as a kid: that my worth or value as a human being is determined not by who I am but by what I accomplish.

The great psychotherapist Alice Miller, in her book The Drama of the Gifted Child, explains that though our parents may have loved us and taken wonderful care of us in many ways, they may also have sent us the subtle message that we are only really lovable if we are great. “You’re so smart,” parents may constantly tell their young children. “Look at how you won,” we then start saying to them, practically by preschool.

Our comments are well-intentioned, but what they convey is clear. We are what we do. We’re worthwhile because we’re outstanding. Which means: God help us if we aren’t. Children might intrinsically value kindness, curiosity, or loving relationships, but all too often we become obsessed with proving how great we are.

This “gifted child” mentality produces industriousness, to be sure; call it The Official Psychopathology of the Protestant Work Ethic. Left unexamined though, it leads us to constantly try to demonstrate our worth by out-working people, out-earning them, and out-greating them. We rarely stop to simply connect with other normal human beings or to allow ourselves to experience vulnerability.

Though it’s hard to feel warmth toward others while stuck in this mindset, we do need to constantly convey it. Because “winners,” remember, aren’t allowed to be naked sociopaths. They aren’t content simply to dominate the capitalist game, now and forever — they have to show you how likable they are while doing so. They have to show how deserving they are of their special status by “doing good,” not just making good.

So we end up with a company like WeWork, the shared office space company and symbol of an unethical tech future. In its recently filed IPO, WeWork said workers were yearning for a “re-invention of work.” Renters at WeWork offices were not clients or customers, but “members,” while neighboring workers were not just colleagues, but part of a “community.” Or so said Adam Neumann, only months before his platinum parachute cash-out, to the tune of $1-2 billion dollars, put the company he founded in such poor financial position that it couldn’t even afford to pay severance to thousands of laid-off employees.

Maybe the contrast between Neumann’s ridiculously communal language and his seeming rank selfishness is an extreme case, but it’s also fairly typical. In the elite social circles known for intellectual discussions of “the future of work,” it’s commonplace to use fancy language to to look not just important but heroic, even as our “innovation” disrupts lives and harms communities.

“How are we doing?” “Not very well.” On loving thy neighbor as thyself

I’m running late to the conference the next morning; I took a little more time playing one of my toddler son Axel’s favorite games: “jumping the shark,” over our living room couch. When Axel was born, I stepped back from my former life as an achievement-obsessed workaholic and encouraged my wife to embrace her busy law career. And not just for its steadier income — I love being Axel’s daily presence, trying to change every single diaper; entertaining his friends when I drop him off at daycare; and holding him tightly in my arms on long daily walks, discussing each new object along our way.

Prayag Narula via MIT Technology Review

Arriving at the Media Lab, I find Narula, who promised before his panel the previous day to describe how startups like his struggle to even attract venture capitalists to human-centered projects these days. He tells me about his friend with a similar business model — ghost work — but who, unlike Narula, doesn’t mention the “human factor” at all in pitches to VCs. The friend, far more successful at such pitches, once confided: “What I pitched to them is, ‘Hey, we are doing this today using people, but it will get automated in the future. And then because we have all this data, we will be the ones automating it.'”

When Narula asked, “do you really believe this can be automated?” his friend responded, “that doesn’t matter.”

“Our economy punishes people that rely on people,” Narula explains. “The education system and thought leaders have created this cascade effect of technologists not taking the human aspect of technology seriously.” I linger too long thinking about his story; now I’m even later for the first morning panel.

As I shuffle into the session, a discussion on the ethics of automation moderated by MIT Technology Review editor David Rotman, Rotman asks, “How are we doing?”

“Not very well,” says Pramod Khargonekar, a distinguished professor of computer science at the University of California.

On the panel with Khargonekar is Susan Winterberg, a fellow at the Harvard Belfer Center’s Technology and Public Purpose Project. Winterberg tells the story of Flint, Michigan’s famous exploitation of its poor, mostly people-of-color citizens, whose water was poisoned while their government abandoned them. Over 70% of Americans live paycheck to paycheck, she then explains.

The Flint Water Plant tower. (Photo by Bill Pugliano/Getty Images)

The number manages to make me the angriest I’ve been at the conference thus far. What can you even call a society whose vast majority doubts the future of their own work, while a small, comfortable minority lives in an almost literally different country? We don’t think of apartheid as something that could happen here, but that’s essentially what took place in Flint between April 2014 and…? Actually, as of this year, an estimated 2,500 lead service lines are still in place.

Winterberg’s talk pivots promisingly, however, to the story of how Nokia executives, including a former Prime Minister of Nokia’s native Finland, worked dutifully and creatively to help their own soon-to-be-displaced workers.

Winterberg’s story, published with Harvard Business School professor Sandra Sucher in a series de HBS case studies, begins in Germany in 2008. Nokia had closed a mobile-phone assembly plant in Germany that year, despite its record profits. The plant was not “cost competitive,” executives explained, with similar work being done in Eastern Europe or Asia.

Factory workers, politicians, and the German public were outraged, generating massive boycotts against Nokia. Unions organized people to ship their Nokia phones back to the company’s international headquarters in Finland. The anti-Nokia campaign cost €700 million in lost sales, Winterberg and Sucher found.

A few years later, after the smartphone revolution made it increasingly clear Nokia’s entire global phone manufacturing business would be decimated, company leadership chose not to abandon workers. Instead, it undertook a massive campaign to help employees cope with displacement, going so far as to stage career fairs and encourage other companies to hire its workers en masse. The campaign’s return on investment, according to the researchers’ analysis, was a thousand to one.

Photo by Josep Lago/AFP via Getty Images

“It’s their values, and it came from the very top of the company,” Winterberg tells me after her panel. “It came from the chairman of the board basically saying, ‘Find a way to do this that treats people with respect, that’s compatible with our values and will help us achieve the transformation we want to achieve, and report back.’”

Listening to her, I can’t help but wonder aloud: was Nokia able to model such solidarity (albeit only after failing in Germany three years earlier) thanks primarily to their roots in a homogenous and affluent society, where it’s a lot easier for management to identify with labor? “Love thy neighbor as thyself,” after all, has since Biblical times generally seemed to work out a lot better when racism and other forms of bigotry were not in play.

But, Winterberg reminds me, Nokia’s magnanimous response was also a global one. They had factories in China, the United States, and other far-flung locations, applying their “bridge program” basically universally. So I ask instead about her own background. From the Cincinnati area, she went to the University of Cincinnati as an undergraduate. There, she was deeply influenced by a field trip to urban Detroit, the degraded state of which made Winterberg want to know, “how could something like this happen?”

Moving on to a Masters in Urban Planning, then work as a researcher at Harvard, Winterberg came to understand the failures of the American Midwest in terms of a kind of unintentionally toxic coastal and economic elitism that has helped Donald Trump. “If you’re living in a small town and don’t have great tech skills,” she tells me, “your future is very dim. (My) presentation is designed to bring you to the experience of the more average person going through this and not just revert to your own experience where (mass layoffs are) basically just a bonus and an inconvenience for a couple of weeks. For most people, this is devastating and a lifelong change.”

Not everyone, in other words, can afford to view the future of work like a game, or from the relatively detached perspective of the typical attendee of a tech conference. And as Winterberg continued about Trump and right-wing populism more broadly, “He understands that from a political point of view. He’s been able to use that. We see that with politicians taking right-wing, populist stances across Europe. Brexit was a couple months before our elections here happened. It was the same thing.”

We’re all implicated, this makes me think. Not too many managers and executives intended to drive middle America into the arms of a Donald Trump. Certainly the centrist economic advisors in the Obama administration didn’t.

But we are all part of a system in which it is just too easy for people of means and privilege to glide along obliviously. It will take enormous, proactive, non-obvious action on our own part to avert disaster. But we’re stuck, deep in denial.

So I leave my conversation with Winterberg feeling sad: for our collective ignorance, and for the rarity of hopeful examples like 2011 Nokia.

To be fair

I find myself recharging as I talk, next, with Walter Erike. Erike, a mid-career independent management consultant also pursuing his MBA at Cornell’s Johnson School of Business, traveled from Philadelphia to attend EmTech Next, hoping to gain insights to inform his consulting business.

Erike, a Black man who spent much of his childhood in Harlem, is somewhat self-conscious about being a visible minority at the conference. But he’s also a dynamo of optimism and positivity.

“I don’t want to pile on MIT,” Erike tells me when I ask him how a conference like this, with a heavily white crowd, could be more relevant to other Black people in tech and related fields. “Because I don’t think it would be fair. But perhaps it would help if they were to reach out to the Urban League, reach out to the National Black MBA, reach out to the Consortium, reach out to NAAP, which is a national organization of Asians, to get more ethnic diversity in the room.”

Not inclined to linger on racial divides, Erike then steers the conversation to the idea of geographic diversity, echoing Winterberg’s concerns about the loss of manufacturing jobs in midwestern America. “If I hear many of the companies in the room, and if I consider where their headquarters are, we’re very West Coast, Silicon Valley focused, and New York, finance focused,” he notices. “There are a lot of really intelligent, motivated Americans living in the center, the Midwest, the breadbasket of America. From what I’ve heard and seen, they’re not represented.”

(My complete conversation with Walter, one of my favorite of the 40+ tech ethics interviews I’ve done for TechCrunch thus far, can be found here.)

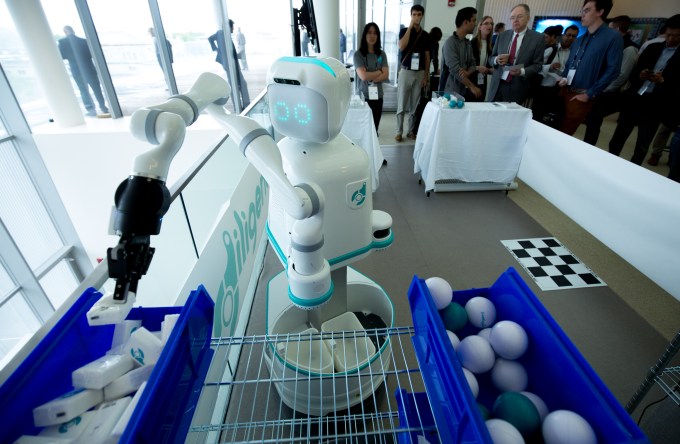

Next I talk with Andrea Thomaz, CEO and Co-Founder of Diligent Robotics. Diligent’s signature invention, a robot prototype named Moxi, is roaming outside of the presentation room. Slightly resembling the maid Rosie the Robot in “The Jetsons,” Moxi is a person-sized presence designed to assist overworked hospital staff. Moxi’s typical day, Thomaz tells me, would be spent trailing doctors and nurses responsible for training it how and when to fetch medicines and other necessary supplies, so they can spend more time with patients.

‘Moxi’ of Diligent Robotics via MIT Technology Review

Thomaz’s product, in other words, may be just the sort of thing to force the cynical critic of AI and machine learning to throw up his or her hands and admit, “you got me.” Who is Moxi hurting? How is it not at least one small part of the solution to real human problems? And then there is Thomaz’s background as a relatively young woman CEO and founder in robotics, with a PhD from the MIT Media Lab and experience teaching at public schools; God knows we need more stories like hers. Like Erike, Narula, Gupta and others, she impresses me as sincere, smart, dedicated to her craft, and determined to pursue it ethically.

Maybe there’s a way towards technological advancement alongside true human decency. Maybe all is not lost yet?

Is ‘Get Hooked’ the Answer?

It’s time to shut the conference down: organizers are peeling “EmTech” logo decals off the walls, but I’m not ready to leave the Media Lab — I need a place to collect my thoughts. Will the work of the future bring ever-ballooning inequality under the guise of what is ultimately the slick, self-serving “philanthropy” of Billionaire Humanism and Winners Take All? Or will the good people I’ve met here at this conference prove not only to be exceptional, but the ethical and inspirational rule?

Bewildered, I begin to wander home. Uber or Lyft are the most efficient way to get from MIT to my house, but I’ve been researching and writing about the ways in which ridesharing is morally compromised. That’s out, given my current mood.

Even a train feels too fast, too claustrophobic, too … technological. So I walk the hour-long route, first through the sleek, monolithic beauty of MIT’s Kendall Square (“the most innovative square mile in the world”) and then through a sleepy industrial neighborhood of tow trucks, a defunct-seeming rail yard, and a multiethnic, working-class population (an area about to be transformed, to the tune of billions of investment dollars, by a coming extension of the Boston metro Green Line train).

Finally, I arrive at Bow Market, a crown jewel of my current home city of Somerville’s ambitious plans for sustainable modernization.

Bow Market opened in the spring of 2018 as a former storage facility turned semicircular courtyard for more than 30 local, independent restaurants, shops, galleries, and even a comedy club. The businesses are mostly women-owned, and the Market’s developers are proud of their nearly 30% minority and 20% non-cisgender owners, too. A quick walk through and you’ll find everything from hand-carved wooden pins of James Baldwin and Zora Neale Hurston to vintage heavy metal t-shirts and motorcycle gear, to grilled pickle pizza and a chocolate mousse in a small chocolate waffle cone that is literally the best thing I have eaten in my entire life.

I go in to Get Hooked, a Bow Market fish shop run by Jason Tucker, a stocky, six-foot-something, grey-bearded New England fisherman with a Bahstan accent. Tucker has a humble, folksy manner and a knack for delicate dishes of lightly marinated blueberry-sized cubes of melt-in-your mouth fish, alongside field greens, citrus, kosher sea salt, and brown rice.

He and his business partner Jimmy Rider started this shop, then partnered with Matt Baumann, a former “money lawyah,” in Jason’s gruff expression, who changed directions several years ago for a career smoking fish. From May to October, Tucker is out on Cape Cod Bay chasing striped bass, mackerel, bluefish, and tuna. And this particular summer Wednesday night, he’s here making $14 bowls for people like me. I take my tuna ceviche in compostable cardboard to a metal table adorned only by a small blue jar. Over the course of my meal, the jar lights up as a sparkly, solar-powered, dark-activated lantern.

The Atlantic’s Derek Thompson, in a 2015 cover story, “A World Without Work,” examined growing research on America’s likely steep decline in jobs in the coming decades. Thompson tells, for example, the story of a 54-year-old writer, grandmother, and former university literature teacher in the post-industrial city of Youngstown, OH, who took a part-time job as a hostess at a cafe, just to stay afloat.

But he also discusses different possibilities, including one scenario he calls “The Artisan’s revenge”: Harvard economist Lawrence Katz’s vision of a world in which 3D printing machines create much of our basic infrastructure, leaving room for a new artisanal economy “geared around self-expression, where people do artistic things with their time.”

Is 3D printing the future of work? Photo by Manjunath Kiran/AFP via Getty Images

“In other words,” Thompson wrote, the future of work “would be a future not of consumption but of creativity, as technology returns the tools of the assembly line to individuals, democratizing the means of mass production.”

So is Get Hooked, and the entire Bow Market in which it sits, the answer? Local working people, applying their crafts with extraordinary artistry, at prices high enough to support a living wage but accessible enough to at least be a very occasional treat for other working-class people, while helping build a diverse, multiethnic, gender nonbinary, social-justice community where an entire city can come together to laugh, to celebrate, to eat, and to ponder important issues?

Or will it ultimately only be people like me, who have the enormous luck and fortune to afford homes in Somerville (current median single family house price: $799,000 and rising) and plunk down $20-plus for a light meal, who are able to enjoy this kind of “artisanal” and “community” experience “sustainably”? Am I doubling down on being part of the problem right now? I don’t know, but I can tell you which way I’m rooting, because that smoked fish is good.

¿Será ético el futuro del trabajo?

I’m happy to admit I don’t know exactly what the future of work ought to be. I am developing my own ever-evolving understanding of what true human dignity and flourishing mean and what a healthier, less dystopian future might look like; I hope to elaborate on it later, including in a book I’ve recently begun to write.