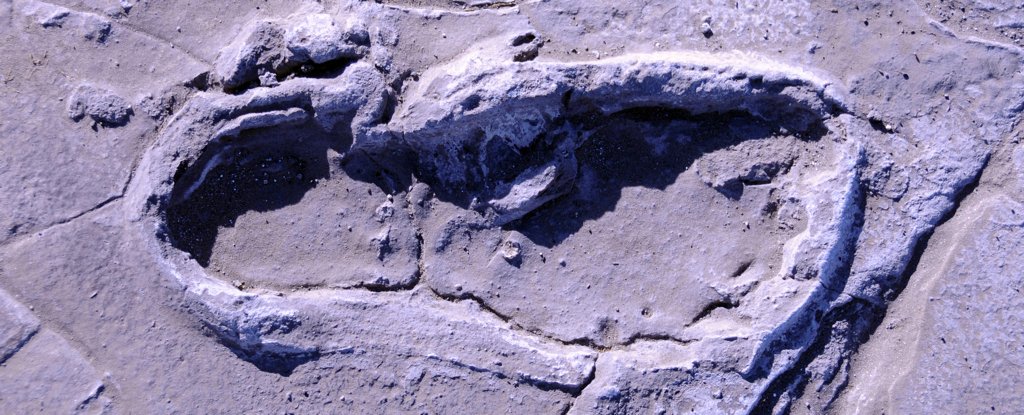

Thousands of years ago, Ol Doinyo Lengai came out. This unique Tanzanian volcano – “Mountain of God”, in the language of the local Masaii people, erupted on an unknown day in prehistoric times, sending a deluge of ashes and lava to its sacred slopes.

The melt, transporting the soil and mixing with the floodwaters of a nearby lake, produced a thick layer of printable mud that settled on the plains below. Shortly after, before the cement mud had a chance to harden, a tribe crossed the nascent mud plane, leaving a record of hundreds of fossilized human footprints that can still be seen nowadays.

This hypothetical sequence of events, which might have seemed something like that – is the best explanation of scientists for what created the largest set of ancient hominin footprints ever discovered in Africa, known as Crimp Sero Footprints.

The Engare Sero footprint site, opposite the Ol Doinyo Lengai volcano. (Cynthia Liutkus-Pierce)

The Engare Sero footprint site, opposite the Ol Doinyo Lengai volcano. (Cynthia Liutkus-Pierce)

in one new study Led by human evolutionary biologist Kevin Hatala from Chatham University in Pittsburgh, the researchers examined these prehistoric impressions, to see what we could discover about the humans who made them millennia ago.

The footprints, first discovered by a local villager, before attracting the attention of researchers in 2008, are estimated to be between 5,760 and 19,100 years old, according to previous survey

.

Previous speculation that the tracks could be much older, dating back 120,000 years – since then it has been restricted by new research.

In any case, what makes Engare Sero special is not so much its age; for this, proximity Laetoli slopes, about 100 kilometers (60 miles) apart, take the cake, which represents what most researchers accept as the oldest footprints on the planet that can be attributed to the first hominids, around 3.7 million years.

On the contrary, what sets Engare Sero apart is the immensity of its collection of preserved tracks: 408 tracks in total, left by a large group of individuals. Who were these ancient Africans and what did they do when they crossed the plains so long ago?

Of course, we will never be able to understand the whole extent of their life and their culture of yesteryear, but it is surprising to see what scientists can capture, reconstruct the details of this extinct community as they walked thousands of years in the past.

Hatala and her team say that all of the footprints were left by barefoot humans, as the individual toeprints are easily recognizable in the footprints.

Among the footprints, 17 sets of tracks appear to have been created by individuals at a moderate walking speed, probably representing a group that was moving together in unison in a southwest direction.

In this group, 14 of the individuals would be adult women, as well as two adult men and a young man.

Another set of six people left footprints moving in the opposite direction and showing a range of movement speeds, with at least two brisk walking evocators and a set of footprints left by one person running of execution.

Due to the difference in speed in this set moving northeast, the researchers suggest that it is unlikely that these six people will travel together.

Although we cannot be completely sure why the makeup of the track manufacturers in general was primarily adult women, the researchers suggest that cooperative feeding activity could be a plausible hypothesis for the tracks we can still see.

"Modern human gatherers are unique among primates in that they generally feed together and in that they generally divide the work between the sexes," the authors noted. explain on your paper.

"In modern human groups such as Ache and Hadza, groups of adult females feed cooperatively, with occasional visits or accompaniment by adult males."

According to the researchers, this could explain the footprints of Engare Sero, which also do not seem to include traces made by children, which would not be surprising if this area was mainly used for the collection of food by people elderly.

"In addition to infants (who are likely to be transported), children are generally excluded from these types of group feeding activities and are left at the camp." the team writes.

The results are reported in Nature.