Real WarGames: How a 1983 exercise almost sparked WWIII

Update, 11/29/20: It’s a very different Thanksgiving weekend here in 2020, but even though tables were smaller and travel didn’t exist, Ars staff are on vacation to recharge, take a mental break, and maybe broadcast a movie or five. But around the same time five years ago, we were following a recently declassified government report from 1990 that described a computer model of the KGB … War games, IRL only. With the film now airing on Netflix (thus establishing our schedule off), we thought of resurfacing for a Sunday reading. This article was first published on November 25, 2015 and appears unchanged below.

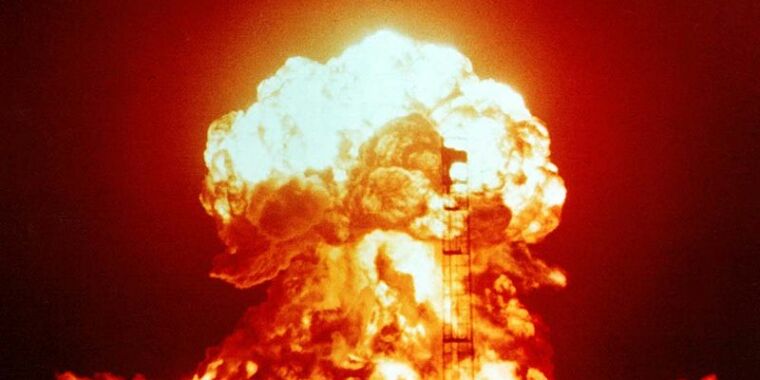

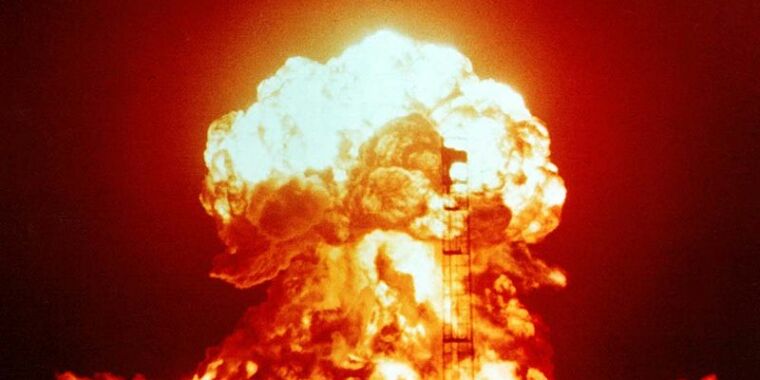

“Let’s play global thermonuclear war”.

Thirty-two years ago, a few months after the film’s release. War games, the world was closer than ever to nuclear Armageddon. In the film version of a global near-death experience, a teenage hacker playing with an artificial intelligence program that has just taken control of the US nuclear missile force unleashes chaos. In fact, a very different computer program run by the Soviets fueled growing paranoia about America’s intentions, and it almost started a nuclear war.

The software in question was a computer model of the KGB built as part of Operation RYAN (РЯН), details of which were obtained from Oleg Gordievsky, the head of the KGB section in London who was also spying for MI6. From Great Britain. Named after the acronym for “Nuclear Missile Strike” (Ракетное Ядерное Нападение), RYAN was an intelligence operation that began in 1981 to help the intelligence agency predict whether the United States and its allies were planning an attack. nuclear. The KGB believed that by analyzing quantitative intelligence data on U.S. and NATO activities in relation to the Soviet Union, it could predict when a stealth attack was most likely.

As it turns out, Exercise Able Archer ’83 triggered this prediction. The war game, which lasted for two weeks in November 1983, simulated the procedures NATO would follow before a nuclear launch. Many of these procedures and tactics were things the Soviets had never seen before, and the entire exercise came after a series of shams by US and NATO forces to assess Soviet defenses and destruction. Korean Flight 007. Air Lines on September 1, 1983. As the Soviet leadership monitored the exercise and considered the current weather, they put on one and one set. Able Archer, at least according to the Soviet leadership, must have been a cover for a real surprise attack planned by the United States and then led by a president perhaps mad enough to do it.

While some studies, including an analysis conducted about 12 years ago by historian Fritz Earth, have downplayed the Soviet response to Able Archer, nail Recently released declassified 1990 report from the President’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board (PFIAB) to President George HW Bush obtained by the National security record suggests the danger was too real. The document has been classified as Top Secret with the keyword UMBRA, which designates the most sensitive compartment of classified material, and cites data from sources which to this day remain highly classified. When combined with Previously published

CIA, National Security Agency (NSA), and Defense Ministry documents, this PFIAB report shows that only the illness of Soviet leader Yuri Andropov – and the instinct of a mid-level Soviet officer – could have prevented a nuclear launch.

The balance of paranoia

While Able Archer 83 was underway, the U.S. defense and intelligence community believed the Soviet Union to be strategically secure. A top secret Joint assessment of the Ministry of Defense and the CIA network published in November 1983 stated: “The Soviets, in our opinion, have clear advantages today, and those advantages should continue, although the differences may narrow somewhat over the next ten years.” However, it is likely that the Soviets did not see their advantage as great as we think ”.

The assessment was fair: the Soviets certainly did not see it that way. In 1981, the KGB’s Foreign Intelligence Directorate performed a computer analysis using an earlier version of the RYAN system, looking for the “global correlation of forces” between the USSR and the United States. The numbers suggested one thing: the Soviet Union was losing the Cold War and the United States could soon find itself in a strategically dominant position. And if that happened, the Soviets believed their opponent would strike to destroy them and their Warsaw Pact allies.

This data was all that management expected given the intransigence of the Reagan administration. The aggressive foreign policy of the United States of the late 1970s and early 1980s troubled and worried the USSR. They failed to understand the reaction to the invasion of Afghanistan, which they thought the United States would recognize simply as a vital security operation.

The United States even funded the mujahedin who fought against them, “training and sending armed terrorists,” as Communist Party secretary Mikhail Suslov said in a 1980 speech (these interns, including a youngster named after Osama bin Laden). And in Nicaragua, the United States channeled arms to the Contras who were fighting the Sandinista government of Daniel Ortega. During this time Reagan refused to involve the Soviets in gun control. This growing evidence convinced some in the Soviet leadership that Reagan was ready to go even further in his efforts to destroy what he would soon describe as the “evil empire.”

The USSR had every reason to believe that the United States also believed it could win a nuclear war. The rhetoric of the Reagan administration was supported by an increase in military capabilities, and much of the Soviet military’s nuclear capabilities were vulnerable to surprise attack. In 1983, the United States was in the midst of its largest military consolidation in decades. And thanks to a direct line to some of America’s most sensitive communications, the KGB had a lot of bad news to share with the Kremlin.

The maritime segment of the Soviet strategic force was particularly vulnerable. The US Navy’s SOSUS (sound surveillance system), a network of hydrophone arrays, has tracked nearly all Russian submarines that entered the Atlantic and much of the Pacific, as well as anti – American submarines. (P-3 Orion patrol planes, fast attack submarines, destroyers, and frigates) were practically above or after Soviet ballistic missile submarines during their patrols. The United States had drawn the ‘Yankee Patrol Boxes“Where Soviet Navaga-class ballistic missile submarines (NATO designation” Yankee “) were stationed off the east and west coasts of the United States Once again, the Soviets knew all this thanks to spy John Walker, so confidence in the survival of his sub-fleet was probably low.

The aerial stage of the Soviet triad was no better. In the 1980s, the Soviet Union had the largest air force in the world. But the deployment of the Tomahawk cruise missile, the initial production of the US Air Force’s AGM-86 air-launched cruise missile, and the impending deployment of the Pershing II intermediate-range ballistic missiles in Europe meant that the NATO could attack. Soviet airfields with very little warning. . Unfortunately, the Soviet Strategic Air Force needed as much warning as it could. The Soviet long-range bombers “remained in a low state of readiness,” the advisory committee’s report notes. It would have taken hours or days to prepare the bombers for all-out war. In all likelihood, the Soviet leadership assumed that their entire bomber force would be trapped on the ground in a stealthy and wiped out attack.

Even theater nuclear forces like the RSD-10 Pioneer, one of the weapon systems that fueled the deployment of the Pershing II in Europe, were vulnerable. They generally did not have warheads or missiles loaded in their mobile launch systems when they were not on alert. The only leg that wasn’t too vulnerable to a NATO first strike was the Soviet Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM) force. However, his availability was in doubt. According to the 1990 PFIAB report, approximately 95% of the Soviet ICBM force was ready to respond to an attack alert within 15 minutes in the early 1980s. The silo-based missiles were out of range. anything other than ballistic missiles launched by American submarines and land-based ballistic missiles.

The viability of the ICBM force in response to a stealth attack was based entirely on the alert time available to the Soviets. In 1981, they brought online a new Horizon Ballistic Missile Early Warning Radar (BMEW) system. A year later, the Soviets activated the US-KS nuclear launch alert satellite network, known as “Oko” (Russian for “eye”). These two measures gave the Soviet command and control structure an approximately 30-minute warning of any launch of US ICBMs. But the deployment of Pershing II missiles in Europe could reduce the warning time to less than eight minutes, and attacks with under-launched missiles by the United States would have warning times in some cases of less than five minutes.

And then President Ronald Reagan announced the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) or the “Star Wars” program, the predecessor of the current Missile Defense Agency efforts to counter limited ballistic missile attacks. While SDI was touted as defensive, it would likely only be effective if the United States drastically reduced the number of Soviet ICBMs fired on the first strike. More than ever, SDI convinced the Soviet leaders that Reagan intended to make a nuclear war against them winnable.

Combined with its ongoing anti-Soviet rhetoric, the leaders of the USSR viewed Reagan as an existential threat to the country just like Hitler. In fact, they made this comparison publicly, accusing the Reagan administration of pushing the world closer to another world war. And perhaps, they thought, the President of the United States already believed that it was possible to defeat the Soviets with a surprise attack.